This is the final instalment in this series. The first post, which is about my childhood, can be found here. You can click the links at the end of each post to follow the series to here.

It seems that September is my month for writing about the ‘big stuff’. Last September, I wrote about my sister’s death. I concluded that piece with:

‘I have these stories tucked away inside my heart where I’ve kept them all this time, sheltered and shielded. Now I unwrap them, one-by-one, these pieces of me.’

This series of posts has been tucked away far deeper than the tale of my sister’s death. Telling this story has felt like stepping into a dark room and forcing myself to stay despite the urge to run. Now I’ve told it, it’s out and can’t be hidden again.

Yet I had to write it—this is my story, the biggest story of my life. It’s been a burden to carry, both as a child and as an adult trying to raise my own family. Each time I’ve sat down to write, this is the tale I’ve wanted to tell. I’ve shied away for many reasons—thinking it was too big, wondering where to start, where to stop, and how to put it all into words. I was fearful of writing publicly about private matters, and I worried that people wouldn’t want to read it.

But, writing it and telling people has brought only relief—I feel as if I’ve unburdened a giant. And each time I read it, more of its intensity ebbs away.

As I’ve written this, I’ve tried to keep my emotions at a distance. In real life, I don’t always manage that. Many times, I’ve felt angry, very angry. I’ve felt sorry for myself and envious of people with nice mothers, and I’ve often wished that my mother was different.

Then I get off my pity pot, put my head down, and get on with it. But it’s been hard to raise a family with this as a backdrop.

Now that I’ve finished telling my story, I’ll let it sit for a while and let it settle. Eventually, I want to pull it apart and put it together again as a summary essay.

Thank you everyone, once again, for your comments, support, and encouragement.

~

We’re easy to spot, we adults who have been abused as children—there’s a vulnerability, a lack of confidence, a sadness about us. You can hear it in the words we say, see the pain in our eyes. And we have a few cracks. We share a bond because we understand something normal people don’t understand, and can’t possibly ever understand, because normal people have no idea what it’s like to grow up with a mother who didn’t love you.

Childhood abuse doesn’t just hurt physically, it’s soul-shattering. As a child, you look to your mother, the most significant person in your life, to learn about yourself. If you’re told you’re bad, that’s what you think you are. When you’re hit, slapped, kicked—words aren’t needed to tell you that you’re worthless and undeserving of respect. If your pants are pulled down and you’re hit while trying to protect the private parts of your body, it’s even worse—that shame and humiliation stays with you forever.

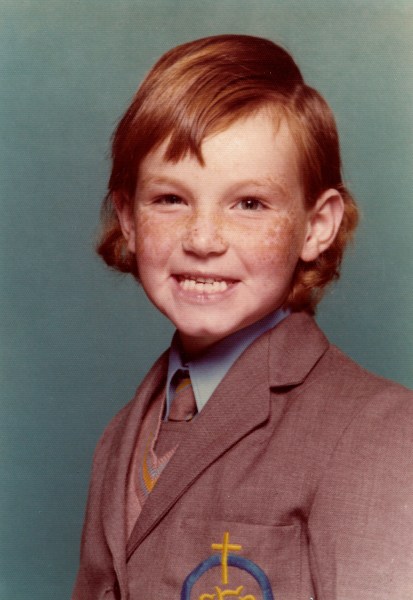

I might have dressed myself this day.

As a child, there was nothing I could do to stop the abuse—I was powerless and there was no escape. I tried to block it out, but there were days when most of my brain was taken up thinking, ‘How am I going to get over this?’ I couldn’t tell a teacher or a relative, let alone Child Protection. If I did try to tell my mother, I was told it was me—I was the problem, it was my fault, and if I behaved better, it wouldn’t happen.

I tried and I kept hoping that one day I might be good enough for it to stop. But I never was. The goal posts would shift, so that reaching them was impossible. Or what was good one day, wasn’t acceptable the next. Or if I brought something up, I was told it didn’t happen, when I knew it did. Or that I’d misunderstood, when I knew I hadn’t.

The abuse didn’t stop—it continued into my teenage years and beyond, and it’s still going. Sometimes I’m so tired of it that it’s hard to put one foot in front of the other and get through the day. I used to try to battle on, but I don’t anymore. These days, I curl up and let the sadness come.

~

Although I was aware that I didn’t have a good maternal role model, I had no idea how hard it would be to mother my children without one. All I knew was that I was determined not to do to my kids what had been done to me.

The pile of parenting textbooks by my bedside grew and I read them all in order to learn how to be a good mother. I took all advice on board and was constantly on edge—if I wasn’t with my baby, I panicked; if my daughter cried, I felt anxious until she stopped. I was trying so hard not to harm her.

At the time, I was unaware of how much of my childhood was being brought back by my children—I didn’t realise that each stage they passed through was triggering my own childhood memories. I wrote once before how the sight of my daughter struggling as she lay across my lap while I cleaned her messy bottom triggered the memory of lying across my mother’s knee, my bare bottom in the air and struggling as she hit me.

I didn’t realise, either, that each time I was attentive to my children’s emotional needs, it brought back what was not done for me.

I had no idea how scarred I was—all I knew was that I avoided anything to do with child abuse. As a doctor, I found it too upsetting. When out and about, I turned away if I witnessed a child being hit. I remember seeing a mother slap her daughter across the face in a supermarket car park. The mother walked off and the child lifted the hem of her dress to dry her tears. I felt hot, my heart raced, and tears flowed as I climbed into my car.

When I had my own kids, this was amplified. I did my best not to hurt my kids, but I couldn’t always stop other people from hurting them, or treating them unfairly, or not recognising their goodness. Each time it happened, my own scars would open, and in I’d slip. Sometimes, I couldn’t pull myself back out and the world would become bleak and painful once again, and I’d be sobbing on the floor.

I’ve spent hours in counselling, reaching into those painful places in my memory and extracting the scenes from my childhood one-by-one. I’ve sat with them and felt their fear and their terror, and let myself feel their pain. Each time I do that, the memory shifts towards a safer place—a place that doesn’t cause my heart to race or my breath to come fast when I think of it. A place alongside all my other memories, where it can sit without terror and without pain.

I still have nightmares about my mother but they’re fewer and only return when I’m forced to deal with her. A few weeks’ ago when my husband told me I’d called out in my sleep, I didn’t tell him that I’d been dreaming about my mother.

My sister and I used to talk a lot about what my mother did to us. I remember my sister telling me that sometimes she wanted to kill herself just to show our mother how much she hurt her. I told her I’d often thought the same.

My brother and I have talked about it. We used to joke about writing a self-help book for abused kids. We had chapters on, ‘How To Cope When Your Mother Beats You For Your Own Good’, ‘How To Cope When Your Mother Rubs Your Nose In Your Own Pee’, and ‘Twenty Things To Do In The Car While Waiting For Your Mother At The Casino’. We had a bonus chapter for parents: ‘How Suing the Government Benefits the Family’.

Behind the humour sat decades of pain, humiliation, and grief.

I wish I could strip away my childhood and start again as a fresh and undamaged child. But I can’t. However, through my children I’ve been able to glimpse my undamaged self—the child who was good and was told she was bad. And mothering my kids gave me the opportunity to mother that child in me. I told the child Louise that she was good, and that what was done to her was wrong. That the pain she’d felt was valid, and that she hadn’t deserved it. And I told the wayward teenage Louise that I forgave her—that she’d been young, and she did the best she could, the only way she knew how at the time: escape.

I think the child Louise nearly believes the adult Louise, but she’ll never fully believe her. There’ll always be a part of her that thinks she’s bad, that if she’d tried harder, behaved better, it wouldn’t have happened.

~

In the last two years, my mother has lashed out at others close to her and has lost not only her children, but other close family members, too. Gradually, I’ve got my extended family back, and I hear more and more of the stories. My mother has also served an uncle with a writ for defamation—the same uncle who stepped in to help my father keep working when his dementia was worsening. Another uncle was threatened with a writ, and continued to receive threatening letters from my mother even after she knew he was dying. And I’ve heard the lies, including that she gave my husband and me $250,000.

There’s relief in knowing that others now know what went on in our family, and that I’m believed. But the sadness outweighs the relief. There’s a sense of loss for all that could have been: for my father, who worked so hard, but didn’t get the life he deserved; and for three beautiful, talented kids, who never knew how good they really were.

In spite of everything, I feel a sadness for my mother—she was intelligent and creative, and could have done so much. Instead, she chose to channel her talents in a destructive way, and has lost almost everything she had, including her family. I feel sorry for her, but I can’t help her.

~

I decided at a very young age that I was not going to pass the baton of abuse on to the next generation—my mother was abused, her mother was abused, and goodness-knows-how-many generations before her were abused. Someone had to stop the cycle.

My children are growing up—one is already grown and has left home—and I’ve done it: I’ve raised a family without abuse. I birthed four beautiful, good children, who are all still beautiful and good. Most of all, they all know their mother thinks they’re beautiful and good.

I carry a sadness that I don’t think will ever completely disappear. And tucked away deep inside, sheltered and shielded, I carry a mother-shaped scar.

But at least my children won’t have one.

Such a powerful story here, Louise. I’m in the middle of Helen Garner’s latest book, This House of Grief, and I can’t help but think about those three children who died, and their father, the perpetrator, and now here you, your sister and brother at the hands of your mother, and then there’s my father, and all those among us who wreak such havoc on those they are meant to love but somehow seek to destroy. There are so many layers to your story and all of them come back to the tragedy of the children, you and your siblings. At least there’s a chance now to redeem the story through your writing, but I’m sorry to hear that your sister and father have not lived to hear this re framing. Write on.

That’s a completely tragic story, Elisabeth. I heard Helen Garner interviewed by Margaret Throsby about it recently. I don’t know if I could read it … Good on you for braving it!

Society expects parents to look after their children, and most do without causing irrevocable harm. Children are so vulnerable—the most vulnerable people in our society. Hurting them is different to hurting adults, because their personalities are forming, their brains are developing. The scars can’t be undone and will last lifelong, and even into the next generation.

I will keep writing about it, but I need to put it aside for a while now and let it settle. Plus, I want to write about other more pleasant things! It’s been wonderful to be able to lift the curtain on this—the best decision I’ve made. It’s like now I’ve got it out of the way, I can begin to enjoy my life!

“I carry a sadness which I don’t think will ever completely disappear. And tucked away deep inside, sheltered and shielded, I carry a mother-shaped scar.”

Once again I’m in tears at the end of this part of your story, just as I’ve been so many times in reading about what you went through as a child. You said to me once something along the lines of me finding joy in life or writing about joyful/positive things… I can’t remember exactly the words you used. I call it my ‘Pollyanna’ moments, looking for the best in things and in people… but I’ve never had to struggle the way you’ve had to struggle, and I cannot imagine how hard it has been.

You are an amazing and generous lady and mother, Louise Allan. I wish you only the best always.

Thanks, Lily. I think I will be able to have more ‘Pollyanna’ moments now that I’ve lifted this giant from my shoulders. I’m so glad I wrote about it, and I’m ready to move on now …

Hello Louise, be so very very proud that the rot stopped with you. That in itself is such an enormous achievement, something that was beyond that generation, thinking of you always xxx

It’s been my major aim in life, Rae! I can’t undo all that was done to me and start afresh, but I set out to make the my children’s pathway through childhood, and through life, a lot easier and happier than mine was. That’s what I set out to do, and so far, it seems to be working!

Thanks so much for your comment. xx

You have broken the chain of abusive parenting and what an accomplishment that is. You are a beautiful person, more compassionate because of your experiences. Louise, your story is beautifully written and well told. Your children are lucky to have a mother like you. You need to publish this for others. Love you.

Thank you, Betty. Your words mean so much to me. My experiences have left me with a few ‘cracks’, and they break apart at times. But, as Karen reminded me below, the Japanese repair their cracked vases with gold. I’d like to think that the gold in my cracks is a degree of understanding, particularly of troubled kids, that I otherwise mightn’t have known.

Hi Louise – what a journey of heartbreak and healing. All that deep work you’ve done has made a different childhood for your own kids; you’ve broken the cycle. That, in my opinion, makes you a genuine, actual, honest to goodness hero. The pen being mightier and all, you’ve written so well of dark and difficult things. Thank you for sharing it with us all.

it brings to mind the Japanese notion of kintsugami or kintsukoroi – do you know it? In principle, it refers to a thing being made more beautiful, more precious, having been broken and repaired, and this history is not to be hidden or disguised but valued. Here’s the fable of Kintsukoro – it is, of course, a good story!

http://philipchircop.wordpress.com/2013/11/10/the-fable-of-kintsukuroi/

Oh, Karen, I’ve just read the fable on the link you gave—such a beautiful story! I love the concept—that something that is broken and has a history is more beautiful than when it was perfect. I don’t know that my history has made me more beautiful, but it’s given me more understanding and compassion. When I was doctoring, I’d occasionally see a young man or woman in shackles accompanied by a prison officer. They’d sit with their eyes downcast, barely looking at me. My heart ached, and I always wanted to tell them how close I came to being them …

I so hope I’ve broken the child abuse cycle. I see our elder daughter out on her own, studying hard, still playing in an orchestra, getting involved with the ‘Close the Gap’ and ‘Doctors for the Environment’. I see our second daughter singing on stage with a poise and a confidence I never possessed, and sticking up for her beliefs even if her peers don’t agree with her. I see our elder son becoming self-assured, writing and playing his music, and off to Hong Kong on Friday to represent his school. And I see our younger son, who still comes up and sits on my knee for a chat before bed, spending his spare time writing a novel that none of us are allowed to read yet. I see them all becoming such good and confident individuals, and I know that I’ve made right decisions to work hard at being a good mum.

My biggest issue is that they don’t clean up after themselves—hence the current spate of Facebook posts! And that’s it, that’s my one complaint, so I really can’t complain!

I too love the Japanese notion of kintsukuroi. It comforts me beyond words.

Yes, and the lyrics to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Anthem’:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

And along those lines, the other day I heard Michael Katakis (a writer and photographer) talking with Margaret Throsby. He’d chosen a Maria Callas song, and they were discussing her voice, which wasn’t perfect. He said that the beauty of art lies in its imperfections. I really love that idea.

Ah yes, Louise, you are filled with light my friend, and it illuminates the dark corners for some of us around you.

I’ve read this final part, but tomorrow would have been Ken’s birthday so I’m not yet able to give my response the focus I would like. Instead I shall share one of my favourite Leonard Cohen songs sung by one of my favourite singers. This 6 part post deserves a Hallelujah.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/kdlang.html

For some reason, Tricia, your comment ended up in spam, so my apologies for taking so long to respond.

Thanks for the song clip—it’s a favourite around here. My son plays and sings it, nearly every day!

I loved your poem for Ken’s birthday, by the way.

Coming from a highly dysfunctional family, an abusive family, is no easy thing and I admire your courage in writing about it. It can’t have been an easy process, and I imagine that each post would have sent a tremor of terror through you, wondering if people would judge you. I understand your pain. Sadly, not everyone is born into a loving family. You’re opening comments ‘we have a few cracks’ and ‘we understand something normal people don’t understand, and can’t possibly ever understand, because normal people have no idea what it’s like to grow up with [parents] who abused you’ is so very true and correct. We try as best we can to paint over those cracks but they are there nonetheless. You’re a courageous woman, Louise, for facing that pain and taking steps to reclaim your life. I wish you all the best with your writing and your healing.

Thank you for your comment, Sonja. I want to reply to everything you’ve written, but I don’t know where to start and it would end up being the length of the blog post!

Firstly, yes, I was worried I’d be judged. Not so much for the actual story, but for daring to tell it. I was worried, too, that people might tell me to ‘just get over it’. But the urge to tell my story was far greater. At the time I wrote it, I knew I was offloading a giant weight, and since then I’ve felt much lighter and much, much happier.

Secondly, I’m glad, but sad, that you agree that people who didn’t grow up with parental abuse can never know how deeply it affects you. It not only affects your childhood, but it’s something you carry with you forever—a sadness, a vulnerability, a hurt because you were never good enough. I think, too, that you can spot those feelings in others who’ve experienced the same.

Thirdly, I like the phrase ‘paint over the cracks’—I certainly tried to cover mine up! Didn’t work—they kept cracking open again, in pretty painful ways. In the end, I had to let them open right up and just ‘bleed’! There’s a much longer story associated with that and I’ll write about it one day, but for the moment, I’ll just say that after being ashamed of my cracks and trying to fix them but not being able to and thinking I was a bad person because I couldn’t, I don’t do that anymore. It’s okay to be an imperfect person—we all are—and I understand and accept my cracks and imperfections now.

Anyway, that’s probably enough to reply to your comment! Thank you again, and I wish you all the best in 2015, and with your own writing. xx

You are a beautiful woman & mother, with a warm loving heart. What courage it has taken to share your journey. I am privileged to have been a small part in your sucess.

Maureen x

Thank you, Maureen, for visiting and for commenting! You are such a precious part of all of our lives. x

How heart wrenching, courageous, powerful, so many things you are. Recently an old friend from school opened up about her past. Her father and the abuse he inflicted on her three siblings and mother. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing because they kept it so well hidden. She is, as you are, a beautiful mother to her children but the pain…..well she still takes it day to day. Such strength you women have, I am in awe.

Thanks again for your reply, Kooky. I’m glad your friend is talking about her childhood—bottled up childhood abuse is just too much to carry. I’m glad you believe her, even though it doesn’t seem in keeping with what you witnessed. Kids cover so well for their parents—partly because they love them despite everything, and partly because of their own shame. I’m glad your friend has someone with whom to share her pain. If she ever wants to talk or write, please let her know she can contact me through this site. Also, since I wrote this series, I’ve learnt a lot more about recovering from childhood trauma, and I can give her the name of a really enlightening book. It helped me more than I can describe.

I will, thank you Louise x

No worries. x