I spent last week at ‘virtual’ Varuna on a writers’ residency that didn’t require leaving home or breaching isolation restrictions, but meant I could mix with other writers, share and discuss writing, and basically feel normal again. It was perfectly timed for me—after five weeks of thinking of very little else other than Covid, I was ready to return to my novel and writing.

The reason I mention this is because, coincidentally, this week’s guest in the attic, Lauren Chater, was also at ‘virtual Varuna’.

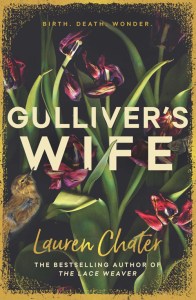

Lauren and I were début authors around the same time and her second book, Gulliver’s Wife, was published this year just as we were all confined to our homes and live events were cancelled. Not to be deterred, Lauren’s been busy doing loads of online events, including launching her book via Facebook Live, which meant I was able to ‘attend’ from Perth. (There are now so many of these types of events happening, and I’d encourage booklovers to join them as they’re a lot of fun.)

Anyway, here’s Lauren to tell you about the inspiration for her book and some of the fascinating history of midwifery:

Lauren Chater is the author of The Lace Weaver, Well Read Cookies: Beautiful biscuits inspired by great literature and, her latest work, Gulliver’s Wife. She is currently working on her third novel, The Winter Dress, inspired by a real 17th century gown found off the Dutch coast in 2014. In her spare time, she loves baking and listening to her children tell their own stories. She lives in Sydney.

You’ll find Lauren on her website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

~

Mother Midnight: In Praise of the Midwife

My mother is a midwife. For years she worked in the maternity ward of our local hospital, leading what often seemed to me to be a strange, nocturnal existence. I remember standing at the window waving goodbye as her car drove off into the night and wondering why she didn’t have a ‘normal’ job like the other mothers I knew.

During the day my sister and I held competitions to see who could stay quiet the longest. Inevitably, we forgot ourselves. One of us laughed loudly or dropped a book and minutes later, my mother staggered out, tousle-haired and bleary-eyed, roaring for silence like a bear stirred from its cave.

I remember my dad explaining afterwards that the work my mother did was ‘important’. The image he conjured of her was something between a good fairy and one of those Victorian nursemaids from children’s books, presiding over rows of cupid-faced infants.

He never told us that the reason she sometimes came home and cried into her cereal was because she’d seen and felt too much, that when women lost their babies to sickness or because of some medical emergency (as they still do, despite all the first-world health benefits we’re so fortunate to enjoy) my mother grieved alongside them.

My parents shielded me from the brutal realities of childbirth – the crucifying pain, the blood, the inevitable risks. When I began working on my latest novel, centred on the experiences of an 18thcentury midwife, I cornered my mother in the kitchen one day, demanding to know why she’d concealed the gruelling details life on the frontline.

‘You never asked,’ she said.

The simplicity of this statement made me reflect on how these women, who play such a pivotal role in our lives, operate mostly in the shadows, carrying out their duties quietly and with minimal fuss. Their contribution to society cannot be overstated and yet, at various stages in history, their profession has been threatened to the point of extinction. For this reason, I set out to unearth the real history of midwifery – one written by women, not their male counterparts – and to highlight their achievements and triumphs.

The midwife has worn many guises over the centuries – herbalist, birth assistant, expert witness brought to court to testify in cases of violent sexual assault. She has weathered allegations of witchcraft and found herself imprisoned for brokering deals with the Devil, accused of trading innocent souls for a chance at immortality. She has seen her reputation, cultivated by years of practical application, torn down by male practitioners with no personal experience of the childbirth process.

As an example, the 17th century physician Nicholas Culpepper, often cited as the ‘father of English midwifery’, relied on second-hand accounts of the process passed onto him by his sister and wife. By the time of his death in 1654, he had, despite fathering six children, never witnessed a single birth. Culpepper’s 1651 treatise A Directory for English Midwives was criticised by the very midwives he hoped to educate, with the women claiming the book was both ‘dangerous’ and ‘desperately deficient’ in its recommendations for emergency procedures.

Yet for all its shortcomings, Culpepper’s midwifery manual was still more credible than the one Dr. William Sermon published twenty years later which was eventually unmasked as an advertising vehicle aimed at encouraging readers to purchase products from his range of diuretic pills.

In England during the 17th and 18th centuries, a campaign to control the way midwives were educated and licensed was resurrected by a member of the Chamberlen family. The Chamberlens were surgeons who’d fled France for England, fearing religious persecution after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Unlike other birth specialists, they possessed a secret weapon in the fight against infant mortality – a pair of iron clamps they called the ‘forceps’. The Chamberlens managed to keep the instrument a secret for 150 years but at the turn of the 18th century, they spied a chance to monetise their invention and establish a firm foothold in the birthing chamber, which had been off-limits to men until that stage.

Once the secret was out, childbirth became a battlefield where midwives and surgeons struggled for control. Midwives weren’t against the use of birthing instruments per se, but they wanted women to be able to give birth in the comfort and safety of their homes and for forceps to be used as a last resort.

They were also concerned about the way care was administered before and after birth. After performing their duty, surgeons took their money and walked away while midwives remained deeply involved in the lives of parish women, often delivering sibling after sibling and providing a variety of homeopathic infant remedies.

Eventually (and probably inevitably), the Barber-Surgeons Guild were eventually granted permission to use their instrument everywhere and midwives ceded the birthing chamber – at least, in theory. I have no doubt they continued working behind-the-scenes, fighting for their clients to be able to access safe conditions in which to raise their families.

Hundreds of years later, women like my mother are the legacy of midwives like Mary Gulliver – quiet achievers who care deeply about their community. They are the women we turn to when our labour pain worsens, when our babies won’t feed, when the nights stretch on endlessly and sleep seems like a distant memory. We owe them our lives – literally.

It’s my hope that when they read this book, they will know how valued they truly are.

~

This week, you can win a signed copy of Gulliver’s Wife, as well as a copy of Natasha Lester’s latest novel, The Paris Secret.

As both of these books are about strong, courageous women, to win them you just have to tell me in the comments here—or on Facebook or Instagram as I’ll check them all!—which woman most inspires you and why. It can be anyone—from the past or present, famous or otherwise—and you don’t have to name just one!

The winner will be drawn at random next Friday, 1st May, at noon WST. Competition is open to Australian residents only.

Natasha was my guest author in the attic this week and she wrote a beautiful post about her father and his illness, and about reading and writing in the time of a pandemic. If you missed it, here’s a link.

Fascinating post. Thank you.

Glad you enjoyed it! Thanks for reading. x

Another terrific piece Louise. I loved this novel and enjoyed reading a bit more about the inspiration and back ground.

So glad you enjoyed this piece, Theresa! Thank you so much for reading. I have Lauren’s book on my bedside table and will be diving in soon! 🙂

You won’t be able to put it down!

I’m really looking forward to it!

So much amazing (and somewhat horrifying) history, things I knew nothing about.

Thanks Lauren and Louise!

Me, too! Lauren always chooses such interesting topics to write about, and her research is impeccable! Thanks for reading, Fi!